Published on 26 May 2025

“Never try to teach a tiger to read; it wastes your time, and it annoys the tiger.”

(adapted from Robert Heinlein)

Developing student reflective practice is becoming a common and increasingly important pedagogical approach in higher education across medical, social work, education and business schools. Reflective practice can improve decision-making and problem-solving, build students’ professional identities and prepare them for a lifetime of learning at work. Yet, as many of us have experienced, teaching reflective practice can be challenging. Undergraduate students can especially be like young “tigers” when faced with reflective practice tasks – confused, skeptical and even downright annoyed. Comments from my first-year business-school students such as “felt like a joke” or “meaningless” are common responses to reflective assessments, leaving me feeling frustrated and in search of better approaches for reflective practice.

Understanding the reflective gap

What explains this mismatch between academic expectations and student engagement with reflection? Longitudinal research (e.g., King & Kitchener, 2004) reveals that most undergraduates, and even some early postgraduates, simply haven’t developed the advanced reflective judgement that we might hope for as educators. The result is a “reflective gap” – a disconnect between academic expectations and what students can deliver in relation to their developmental capacity.

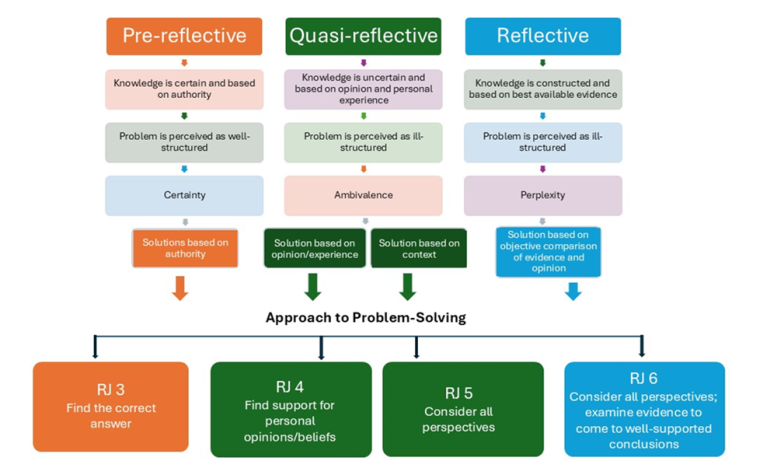

King and Kitchener’s (2004) Reflective Judgement Model (RJM; Figure 1) provides a useful lens for understanding this developmental journey. The RJM describes three sequential stages of reasoning:

- Pre-reflective: Students see knowledge as certain, dislike ambiguity and rely heavily on authority figures for answers.

- Quasi-reflective: Students acknowledge some uncertainty and can recognise multiple viewpoints, but struggle to integrate them into broader perspectives. They use others’ opinions and their personal experience to fill knowledge gaps.

- Reflective: Students can critically evaluate evidence, synthesise holistic perspectives and remain open to changing their conclusions when new information emerges.

Many undergraduates begin university at the pre-reflective stage, with typically slow progress toward quasi-reflective thinking. Full reflective capacity, which is characterised by complex evidence-based reasoning, often emerges only during postgraduate study or later adulthood. Also, students in the same age group can be at different developmental stages and need tailored support for their reflective learning.

A developmental approach

Given this developmental trajectory, how can we foster meaningful reflective practice? The key lies in designing reflective tasks that are aligned with student developmental progression and scaffolded for their learning.

For undergraduates, this means starting with simple, content-based reflection and helping them distinguish between external perspectives and their own thoughts and feelings (Grossman, 2009). For first-year students, I recommend the “Stop/Continue/Start” method (e.g., Hoon, Oliver, Szpakowska & Newton, 2015), as it lets students express their feelings and reduces the uncertainty of open-ended reflection that can be so intimidating for them. The ‘Stop’ element lets students consider what’s not working and express their feelings. The ‘Start/Continue’ element helps them generate practical improvement ideas, which in turn builds confidence in their reflective abilities. If you think this approach sounds too simplistic, consider that Netflix uses “Stop/Start/Continue” in their employee performance-management system – integrating the model directly into 360-degree reviews.

Other straightforward process frameworks, such as Gibbs's (1988) reflective cycle and Rolfe et al.’s (2001) "What-So What-Now What" model, give structured ways for students at all developmental stages to reflect on their experiences. More sophisticated frameworks, like Schön's (1987) concepts of “reflection-in-action” and “reflection-on-action”, are useful for students at higher stages of development.

Reflective essays, learning portfolios, mentoring and workshops are often incorporated into curricula to build reflective thinking and scaffold student practice. Several contextual factors need to be addressed for these activities to be successful; these can include:

- A positive, non-judgemental environment for students to share their reflections with peers and teachers;

- Clear guidelines for reflection and providing stimulating questions from teachers or mentors;

- Autonomy for students to develop authentic reflections; for example, through offering options and topics that align with their interests and preferences; and

- Reflective activities that are scheduled outside of stressful academic periods to avoid their being perceived as yet another annoying burden.

Another key issue to consider is whether reflection as a developmental capacity should be assessed through traditional grading or via a “met/not met” competency framework. I would advocate for a competency-based approach that acknowledges developmental diversity, and motivates students to focus on their growth, rather than performance. Competency-based rubrics with clear descriptors (e.g., “beginning”, “developing” and “accomplished”) could be used for assessment instead of letter grades.

Fostering student reflective practice requires patience! Pushing students too quickly beyond their reflective capacities may only risk “annoying the tiger”. Instead, it’s more effective to meet students where they are and provide carefully scaffolded learning approaches to encourage reflective growth.

***

Reading this on a mobile? Scroll down to read more about the author.